Segments of society. Social segmentation. Social space, social distance, social position

|

Segmentation signs |

Segmentation characteristics |

|

Income level (monthly) |

Less than 500 rubles; 501-1000, 1001-1500; 1501-2000, etc. |

|

Social class (layer) |

Employee; farmer; entrepreneur; employee; student |

|

Occupation (profession) |

Worker; engineer; historian; company managers, etc. |

|

Education |

Initial; unfinished average; the average; specialized secondary; incomplete higher education; higher |

|

Religion |

Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, other |

|

Nationality |

The British; Germans; Russians; Hungarians, etc. |

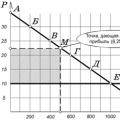

To the greatest extent, the consumption of certain goods and services, and, consequently, the behavior of the buyer in the market is determined by the level of his income. Than big financial resources possesses the consumer, the wider his opportunities both in terms of meeting specific needs, and the structure of these needs.

Income growth is not always accompanied by an increase in the number of consumed goods of a particular name or group. For example, as income rises, the share of spending on food tends to decrease and spending on cultural needs rises.

The demand of the buyer-worker or economist, their behavior in the market can also differ significantly, because the professional interests of people leave their mark on the motives for purchasing a particular product. Professional interests are formed in the process of education. However, it often happens that people with the same education have different professions. On the other hand, you can improve your education level without changing your profession. In both cases, a reorientation of purchasing behavior is possible.

In the last decade, there has been a polarization of the Russian population in terms of income. A stratum of citizens has formed in the country with unlimited paying opportunities, which is ready to pay high prices for goods with special consumer properties (steamed veal or lamb), for high-quality fruits and vegetables, organic food, etc.

The solvency of the bulk of the population (workers, small employees, teachers of educational institutions, scientists, etc.) is limited by the ability to purchase a certain set of foodstuffs necessary for health. A special segment of the market is formed by retirees, unskilled workers, single-parent families, students and pupils.

The signs of socio-economic and demographic segmentation can be combined into more complex parameters of the segments.

Geographic, demographic and socio-economic segmentation criteria refer to the groupobjective signs , and in practice they are not enough. For a more accurate segmentation of markets, we use subjective signs - psychographic and behavioral.

SEGMENTATION BY PYCHOGRAPHIC PRINCIPLE

Psychographic segmentation combines a whole set of characteristics. The personality type of buyers, their subjective assessment of goods, consumption habits, lifestyle, can provide a more accurate characterization of the possible reaction of buyers to a particular product than quantitative assessments of market segments by demographic or socio-economic characteristics. This manifests itself in personal hobbies, actions, interests, opinions, a hierarchy of needs, the dominant type of relationship with other people, etc. ( table.).

table.

2. MARKET SEGMENTATION AND PRODUCT POSITIONING.

2.1 Breaking the underlying market into pieces.

The firm, releasing a specific product, focuses it on the consumer. Knowledge of its consumer is necessary for a company in order to better adapt to its requirements and most effectively gain a foothold in the market.

A firm can build its activities on two approaches: market aggregation and differentiation. The first approach assumes that the firm produces one or more types of goods intended for a wide range of consumers.

Practice shows that different consumers have different attitudes even to the same product. Consequently, the same product can be offered to different groups of consumers. A differentiated approach and involves dividing the market into separate segments.

Whatever the consumer audience, it is almost never a homogeneous aggregate, but consists of thousands, millions of individuals, differing in tastes, habits, and requests.

The breakdown of buyers (consumers) into separate, more or less homogeneous groups is called segmentation.

A market segment is a group of consumers characterized by the same type of response to offered products and to a set of marketing incentives.

The objects of segmentation are consumers.

The goal of segmentation is to maximize customer satisfaction in various products, as well as rationalize the enterprise's costs for the development of production programs, release and sale of goods.

A prerequisite for segmentation is the heterogeneity of customer expectations and customer states. The conditions for implementing segmentation are as follows:

- the firm's ability to differentiate the marketing structure (prices, sales promotion methods, point of sale, products);

- the selected segment must be sufficiently stable, capacious and have a growth perspective;

- the firm must have data on the selected segment, measure its characteristics, study the requirements;

- the selected segment must be accessible to the firm;

- the firm must have contact with the segment;

- the firm must be able to assess the protection of the selected segment from competition, determine the strengths and weak sides competitors and their own competitive advantages.

Segmentation allows you to:

- to determine the advantages and weaknesses of the company itself in the struggle for the development of this market;

- more clearly set goals and predict the possibilities of a successful marketing program.

The disadvantage of segmentation is to determine the high costs associated with additional market research, with the preparation of marketing programs, the use of various distribution methods.

In a modern market economy, each specific product can be successfully sold to certain segments of society, and not to the entire market, therefore, it is impossible to do without segmentation.

2.2 Segmentation strategies.

By segmenting the market, each company solves two issues:

- How many segments should you cover?

- How to determine the most profitable segments for her?

Answering the questions posed, the firm must take into account the goals that it sets for itself, available resources, production capacity. When solving the questions posed, one of three strategies should be chosen, namely:

- mass marketing;

- concentrated marketing;

- differentiated marketing.

Choosing a strategy mass marketing the company enters the entire market with one type of product. This is a big sales strategy when the company's goal is to maximize product sales. In this case, high costs are required. This strategy is used by large enterprises. The methods of mass distribution and mass advertising are used, one generally recognized price range, a single marketing program targeted at various consumer groups. As the market becomes saturated or competition grows, this approach becomes less productive.

Concentrated marketing assumes that a firm focuses on one segment of the market. It is used by small firms with limited resources, focusing efforts in the direction where it has the opportunity to use its advantages. The company's marketing strategy is based on the exceptional nature of its products (for example, exotic products aimed at wealthy consumers, special clothing for athletes). With this strategy, the influence of competitors is dangerous and the risk of large losses is significant.

The third strategy is to cover several segments and release their own product for each of them. This is a strategy differentiated marketing. Each segment has its own marketing plan. The release of a large number of various goods by assortment and types requires and high costs for development work, distribution and trade network, advertising. At the same time, this strategy allows you to maximize the sale of products.

2.3 Types and criteria of segmentation.

Market segmentation requires detailed knowledge of consumer requirements for a product and the characteristics of the consumers themselves. There are several types of segmentation:

- macro-segmentation - division of markets by region, country, their degree of industrialization, etc.

- micro-segmentation - the selection of a group of consumers according to more detailed criteria.

- Depth segmentation, when a marketer begins segmentation with a wide group of consumers, and then deepens, narrows it (for example, wristwatches - watches for men - watches for business men - watches for business men with a high level of income);

- preliminary segmentation - coverage of a large number of possible market segments intended for study at the beginning of marketing research;

- final segmentation - determination of the most optimal, with a limited number of market segments, for which the market strategy and program will be developed. The final stage of market research.

Market segmentation can be performed using various criteria and attributes.

A criterion is a way of assessing the validity of the choice of a particular market segment for a company, a feature is a way of identifying a given segment in the market. The following segmentation criteria are distinguished:

- The quantitative parameters of the segment. These include the capacity of the segment, i.e. how many products and what total cost can be sold, how many potential consumers there are, what area they live on, etc. Based on these parameters, the company must determine what production capacity should be focused on this segment, what should be the size of the distribution network.

- Segment availability for the company, those. the ability of the company to obtain distribution and marketing channels for products, conditions for storage and transportation of products to consumers in this market segment. The firm must determine whether it has a sufficient number of distribution channels for its products (in the form of resellers or its own distribution network), what is the capacity of these channels, whether they are able to ensure the sale of the entire volume of products produced taking into account the capacity of the market segment, whether the delivery system is reliable enough products to consumers (whether there are roads and which ones, access roads, cargo handling points, etc.) Answers to these questions give the company's management information to decide whether it has the opportunity to start promoting its products.

In the selected market segment, or still have to take care of the formation of a sales network, establishing relationships with resellers or the construction of their own warehouses and stores.

- Opportunities for further growth, i.e. determining how realistic a particular group of consumers can be considered as a market segment, how stable it is in terms of the main unifying features. In this case, the company's management will have to find out whether this market segment is growing, stable or decreasing, whether it is worth orienting production capacities to it, or, on the contrary, it is necessary to re-profile them to another market.

- Profitability... On the basis of this criterion, it is determined how profitable the company will be to work for the selected market segment.

- Segment compatibility with the market of major competitors... Using this criterion, the management of the company should get an answer to the question to what extent the main competitors are ready to sacrifice the selected market segment, to what extent does the promotion of this company here affect their interests? And if the main competitors are seriously concerned about the promotion of your company's products in the selected market segment and take appropriate measures to protect it, then be prepared to incur additional costs when targeting such a segment or look for a new one, where competition will be (at least initially) weaker ...

- Efficiency of work for the selected market segment... This criterion is understood, first of all, to check whether your company has proper experience in the selected market segment, as far as engineering, production and sales staff are ready to effectively promote products in this segment, as far as they are prepared for the competition. The management of the company must decide whether it has sufficient resources to work in the selected segment, determine what is lacking here for effective work.

- Possibility of communication with the subject... The firm must be able to constantly communicate with the subject, for example, through personal and mass communication channels.

Only after receiving answers to all these questions, assessing the potential of your company by all (and not by any one) criteria, you can make decisions as to whether or not this market segment is suitable for the company, whether it is worth continuing to study consumer demand in this segment, continue to collect and process additional information and spend new resources on it. The listed criteria are also important in the case when a firm analyzes its positions in a previously selected market segment.

When segmenting the consumer goods market, geographic, demographic, socio-economic, psychographic, and behavioral characteristics are usually taken into account.

When segmenting the market by geography, it is advisable to consider groups of buyers with the same or similar consumer preferences, determined by their residence in a given territory:

Market segmentation by demographic suggest dividing it into separate groups, taking into account such factors as gender, age, family size, its lifestyle:

Psychographic signs are believed to better understand consumer motives, which makes it possible to better adapt the product to the requirements of a particular market segment. They take into account social status and lifestyle. Life style Is a global product of the personal value system, its relationships and activity, as well as its ....... consumption. It is an aggregated indicator based on various methodologies. In the course of research carried out in various countries, many different lifestyles have been identified. Their diversity is determined by the objectives of the research, the studied variables, the methods of collecting and processing information. Lifestyle styles can change over time.

Segmentation variables |

Socio-economic indicators |

Social status |

Low, medium, high (can be detailed) |

Life style |

In the early 90s, French experts identified the following social styles:

|

When segmenting the market on a socio-economic basis, first of all, groups of buyers are distinguished, taking into account the level of income, belonging to a social class, profession:

Segmentation variables |

Socio-economic indicators |

Income level (monthly) |

Less than 100 thousand, 101 - 250, 251 - 400, 401 - 600, 601 - 800, over 800 thousand |

Social class |

Workers state enterprises, workers of private enterprises, collective farmer, farmer, entrepreneur, individual sector worker, office worker, creative intelligentsia, technical intelligentsia, student |

Profession (occupation) |

People of mental and physical labor; managers, officers and owners of the firm; people of creative professions; workers and employees; industrial and agricultural workers; pensioners; students; housewives; unemployed |

The level of education |

Primary or less, incomplete secondary, secondary, incomplete higher, higher, postgraduate education. |

When segmenting the market by behavioral trait groups of buyers are distinguished depending on their knowledge, relationships, nature of use and reaction to this product:

Segmentation variables |

Consumer habits |

Shopping frequency |

Regular, special |

Seeking benefits |

Product quality, service, economy, prestige |

Consumer type |

Non-consuming, previously consuming, potential consumer consuming for the first time |

Consumption rate |

Weak consumer, moderate consumer, active consumer |

Degree of commitment |

None, weak, medium, strong, absolute |

The degree of readiness for the perception of the goods |

Lack of awareness, awareness, awareness, interest, desire, intention to acquire |

Product attitude |

Enthusiastic, positive, indifferent, negative, |

When segmenting the market for goods for industrial purposes the priority is given to economic and technological features and, first of all, the following are used:

- branches (industry, transport, agriculture, construction, science, culture, healthcare, trade);

- field of activity (R&D, main production, industrial infrastructure, social infrastructure);

- enterprise size (small, medium, large);

- geographical location (tropics, extreme north);

- psigraphic (personal and other characteristics of decision-makers in the company);

- behavioral (the degree of formalization of the procurement process, the duration of the decision-making process).

When selecting the optimal market segments, it is recommended to give preference to the largest segments, segments with clearly defined boundaries and not intersecting with other market segments, segments with new, potential demand, etc. It is considered to be the most optimal segment, where there are about 20% of buyers of this market, purchasing about 80% of the goods offered by this company.

2.4 Steps: Initial segmentation, selection of target markets.

The segmentation process consists of the following stages:

- Formation of segmentation criteria;

- Method input and implementation of market segmentation;

- Interpretation of the received segments;

- Selection of target market segments;

- Product positioning;

- Marketing plan development;

When forming the criteria for market segmentation, it is necessary to determine who are the main consumers of the product, what are their similarities and differences; determine the characteristics and requirements of consumers for the product.

When choosing a segmentation method, special classification methods are used according to the selected characteristics. The choice of the method is determined by the goals and objectives of the researchers. The most common method of grouping by one or more characteristics and methods of multivariate statistical analysis.

The interpretation of the received segments consists in the description of the profiles of the consumer groups (the received segments).

After dividing the market into separate segments, it is necessary to assess the degree of their attractiveness and decide on how many segments the company should focus on, i.e. select target market segments and develop a marketing strategy.

One or more segments selected for the marketing activities of the enterprise represent the target market segment. In the process of forming a target market, firms can focus on market niches and market windows.

A market niche is a segment of the market for which the product of a given firm and its supply capabilities are the most optimal and suitable.

Market window - these are the market segments that have been neglected by the manufacturers of the relevant products, these are the unmet needs of the consumers. The market window does not mean a shortage in the market, it is a group of consumers whose specific needs cannot be directly satisfied with a specially created product for this, but are satisfied as a result of the use of other products.

The firm can use concentrated or dispersed methods to find the optimal number of target markets.

Concentrated the method assumes the sequential development of one segment after another, or until a sufficient number of segments is mastered for the company. Moreover, if one of them turns out to be unprofitable, then they refuse it and start working on the next one.

The dispersed method presupposes entering at once the maximum possible number of market segments in order to be able to select the most attractive and abandon the unpromising ones, bringing the number of segments in which the company will operate to the optimal level. The dispersed method requires less time to implement than the concentrated method, but requires significantly higher one-time costs.

Let us consider possible strategies for selecting target market segments using the example of organizing cable television. The market of information services of this type can be segmented according to two criteria, dividing each of them into three levels. The first sign is age with levels: children (D), middle age (C) and pensioners. The second segmenting feature is consumer preference with levels: cognitive programs (CP), entertainment programs (RP), and feature films (HF). In this case, the segment matrix consists of 9 elements and there are 6 possible ways to enter this market.

| a) concentration on a single segment | b) focus on consumer preference | c) focus on the consumer group | |||||||||

| d) selective specialization | e) full coverage of the segmented market | f) mass marketing | |||||||||

Fig. 1 strategies for choosing a target market.

Strategy a) - concentrated marketing, strategies b), c), d), e) - variants of the differentiated marketing strategy, strategy f) - mass marketing. The order in which market segments are established should be carefully considered as part of a comprehensive plan. This procedure is not algorithmic, but is largely a creative process.

2.5 Positioning, Target Marketing Program

Having determined its target market segment, the company must study the properties of the image and products of competitors in order to assess the position of its product on the market and the possibility of penetrating this segment. If the segment is already established, then there is competition on it and they have taken their “positions”.

The firm must evaluate the positions of all competitors in order to determine its own positioning, i.e. ensuring a competitive position of goods on the market.

Positioning a product in a selected market is a logical continuation of finding target segments, since the position of a product in one market segment may differ from how it is perceived by buyers in another segment.

Table 1.

Determining the position of the product on the market (using the example of a component part for the automotive industry)

Some Western marketers consider positioning within the framework of sales logistics, it is defined as the optimal placement of a product in the market space, which is based on the desire to bring the product as close as possible to the consumer. Advertising professionals use the terms “positioning” to refer to the selection of the most advantageous position of a product in a product display. In any case, product positioning is the determination of the place, position of the product in relation to those already on the market. The place of the product is found by comparison. Comparative analysis can be carried out, for example, according to the scheme presented in table 1.

The indicators of the scheme can be changed, supplemented, adapted to a specific situation, typical for the company and the manufactured product.

There is also a known method of drawing up functional maps based on drawing up three types of maps:

- Product positioning map

- Consumer preferences map

- Summary map

Positioning and segmentation are closely related concepts. The positive impulse of the company itself positions the product, that is, the buyer believes the brand of the company.

Further, for each market segment, a target marketing program is developed according to the 4xP principle (product, promotion (advertising, direct sales, sales promotion, public relations)). The practical meaning of segmentation is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

| Marketing mix |

Mass marketing |

Concentrated marketing | Differentiated Marketing |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Target market |

Wide range of consumers | One well-defined consumer group | Two or more defined consumer groups |

| Product or services (Product) |

Limited number under one brand name for many types of consumers |

One brand of goods or services tailored to one group of consumers | A distinctive brand of goods or services for each consumer group |

| Price (Price) |

One “widely recognized price range " |

One price range, adapted for one group of consumers |

A distinctive price range for each consumer group |

| Sales (Place) |

All possible outlets | Only suitable outlets | All suitable outlets are different for different segments |

| Promotion | Mass media | Suitable media | Suitable media are different for different segments |

| Focus on strategy | Targeting different types of consumers through a single broad marketing program | Targeting a specific consumer group through a highly specialized but massive program | Targeting several different market segments, through different marketing plans tailored to each segment |

Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Like the individuals of all those animal species, which are more or less characteristic of a group way of life, the human individual already at the moment of birth becomes a member of a certain society, organized in accordance with certain rules of community. To simplify the picture, we can say that in animals these rules are dictated mainly by evolutionarily developed programs of intraspecific communication, in humans - by cultural traditions specific to a given ethnos. That social organism, into the fabric of existence of which the life of each of us is woven from birth to the hour of death, we are accustomed to call society. Being in this sense a brick of our everyday language, the word "society" in the human sciences acts as a special term, becoming one of the fundamental concepts of philosophy and sociology. Here we use the terms “society” to denote a certain type of social organization that has developed on the basis of a certain culture and, once formed, itself supports the existence of the latter and its development.

There is no doubt that the method of social organization practiced in a particular human society is largely determined by the ecological conditions of a particular natural environment, which people have to master in their life interests. However, the fact that in the same natural conditions societies with a fundamentally different social structure can exist indicates the enormous role of traditions, that is, the spiritual principle, as the reasons for the uniqueness of this system of social relations. Since the world of traditions of each ethno-sa is absolutely unique, because its formation in the history of the people, in principle, is not subject to the laws of logic, the very assumption of the possibility of the existence of some universal type of human society would be at least naive.

Diversity of societies and their classification

Strictly speaking, it would not be difficult to expect a diversity of societies, comparable to the diversity of ethnic cultures, which is truly grandiose. According to rough estimates, at present there are from 4 to 5 thousand independent ethnocultural formations on the planet. Even with a cursory glance at the striking diversity of existing human societies, coupled with those that did not stand the test of time and gave way to others, an analogy with cosmic stellar systems involuntarily suggests itself. Indeed, both giant stars and dwarf stars have been and still exist here and there. In the process of ethnogenesis, some communities of people eventually fade away, like cooling luminaries, others gain vital energy, turning from a modest grouping of mortals into a powerful state, shining like a star of the first magnitude in the firmament of its contemporary interstate relations.

Everything that is now known about the history of human relationships on our planet testifies to the striking unevenness of the evolution of human societies - whether it happened in Eurasia, in the New World or on the African continent. In particular, according to the French cultural critic J. Balandier, pre-colonial Africa “... is the most unusual laboratory that experts in the field of political science could only dream of. Between societies organized in roving groups (pygmies and negrilli) and societies that have already created a state, there is a wide range of political entities. Societies with "minimal" power are very diverse, where balance is created by constant interaction between clans and tribal groups (lineages) and the strategy of marriage unions. More or less complex pre-state societies are known ... The traditional state is also represented in very different guises ”[Balandier, 1984].

In fact, the ideas about the world of each of the ethnoses that have gone into the past, as well as all the existing ones, represent their own bizarre, unique alloy of traditions, attitudes and beliefs, rooted both in the centuries-old practical experience of this people, and in truly countless ones, legalized over the centuries. delusions of reason. As the French philosopher A. Bergson wrote, "But about sapiens, the only being endowed with reason, is also the only being that can make his life dependent on deeply unreasonable phenomena." The microcosm of the ideas about the universe that have developed in the depths of the ethnos with the cults and rituals that follow from this, as well as the rules of behavior of people in their private life and in relations with other members of society - all this together constitutes the spiritual basis of this unique culture. Its second, material half is made up of the tools of labor characteristic of a particular ethnic group, the skills of their use and the products of self-support obtained in the process of activity.

With all the colossal diversity of ethnic cultures and the corresponding methods of social organization, many variants of the social structure differ only in particular details, which makes it possible to combine fundamentally similar variants of social structures into certain prefabricated groups (or classes) and to compare the latter with each other. Such a procedure for classifying societies is far from simple, so it is not surprising that different researchers are often guided in this work by different principles and approaches.

The most common principle of classification, where it is based on such a property of society as the degree of development of the power of some of its members over others. With this approach, societies are concentrated at one pole in which power structures and functions are reduced to a minimum or are absent altogether. These are the so-called anarchist, or egalitarian societies (from the French egalite - "equality"). At the other extreme, we find all sorts of variants of totalitarian societies with a despotic system of control of an authoritarian personality (dictator) and a bureaucratic minority over the bulk of the population. In the latter case, we have before us the principle of the state structure, brought to its logical conclusion, as an apparatus of violence by the ruling elite over the minority, which is infringed upon its rights. Between these two poles are all sorts of pre-state societies - with immature mechanisms of centralized power and moderate social inequality, as well as states based on the principles of democracy and parliamentarism.

Another way of classifying societies emphasizes differences in their basic structural features. With this approach, three types of societies can be distinguished: segmental, stratification and synthetic. What it is? Segmental structure in its structure can be likened to the so-called modular organisms, which are built, as it were, on multiple “repetition” of similar parts (“modules”) that perform similar vital functions.

Such are, for example, reed clumps connected to each other by an underground rhizome, or “segments” (metameres) of the tapeworm-tapeworm, each of which is a more or less self-sustaining semi-autonomous system. Stratification societies get their name from the Latin stratum (literally “layer”). A society of this type is easiest to imagine in the form of a puff cake, so that all kinds of interactions between layers (strata) are organized more horizontally than vertically. And, finally, synthetic I call the current industrial society, in which all functional subsystems that fulfill its needs (politics, economy, science, religion, education, etc.) merge into a single complex mechanism that enslaves, in essence, with its inexorable the human masses serving him. Before our eyes, the next step is also taking place - the merger of such industrial societies into a single global, world society, which, in contact with segmental and stratification types, quickly destroys them, engaging more and more ethnic groups in the mad race of "modern mass society".

Since the two considered variants of the classification of societies put different criteria at the forefront, these classifications are not mutually exclusive, which makes it possible to combine the categories they offer. Thus, segmental-type societies most often turn out to be simultaneously anarchic, and the state structure in its most developed forms is characteristic of synthetic industrial societies. However, combinations of features provided by both classification options can be very different and sometimes very bizarre. Thus, in the Kingdom of Nepal, the caste system (a typical variant of a stratified society) dominates the centralized state power, in which ethnoses of hunter-gatherers are involved as its edge elements, whose social organization retains all the features of an anarchic segmental society.

Segmental type societies

A typical example of this type of society is provided by the social organization of the South American Nambiquara Indians, who live in the dry shrub savanna (the so-called brusse) of southwestern Brazil. These Indians do not wear any clothing, except for a thin thread of homemade beads that hangs around the waist of the women. Men sometimes cover their genitals with a straw tampon, but do not use the so-called sex cover, which serves as an indispensable part of the male "wardrobe" for most of the Indian ethnic groups in Brazil, as well as in many other primitive cultures of the world. The lack of clothing is compensated by a variety of beads and bracelets (from the shell of an armadillo, straw, cotton fibers, etc.), and men's jewelry often looks more elegant and festive than that of the fair sex. At the beginning of this century, the number of Nambikvar was about 20 thousand people. In the mid-60s, according to data The World Organization health care, Nambiquara were among the endangered peoples - along with one and a half to two dozen other ethnic groups living in the tropical forests of South America, Africa and Southeast Asia.

Spatial structure. In their existence, Nambiquara are completely dependent on the autocracy of the surrounding nature. Based on their centuries of experience, these people learned to anticipate her whims, which enabled them to survive - despite the constant pressure on them from the harsh, if not to say - aggressive environment. In the dry season, which lasts from April to September, the necessary food can be obtained only by constantly moving in small groups (up to 20-30 people, connected by ties of kinship) through the vast expanses of inhospitable bars. With the onset of the rainy season, several such groups, connected with each other by a network of kinship, settle somewhere in an elevated place near the river bed. Here, the men jointly build several primitive round huts from palm branches. During this time, hunting and gathering, which provided food during the dry season, gave way to slash and burn farming. Near the village, the Indians burn out areas of lush vegetation, and in the glades reclaimed from the forest they set up modest gardens, barely able to feed the population of the village of up to a hundred people for almost six months. Nambiquara gardens grow cassava, from the tuberous roots of which women make starch-rich flour, as well as corn, beans, pumpkins, peanuts, cotton and tobacco, which is used for smoking by both men and women. With the onset of the next dry season, the community again splits into groups, each of which goes on a long and difficult journey.

So, we see that the Nambikvar's society is built of segments of the same type, in fact. During the rainy season, such segments are communities tied at this stage of their existence to temporary forest “villages”. In the dry season, Nambiquara society is represented by roving groups widely scattered over the vast expanses of the brusse. Thus, here we have at least two hierarchically subordinate levels of community organization. The higher level is the "agricultural" communities, the lower nomadic groups, which are nothing more than fragments of these very communities.

K. Levi-Strauss, who studied in detail the way of life of nomadic groups, argues that there is hardly a social structure more fragile and ephemeral than a collective of this kind. “Individuals or entire families,” writes the scientist, “separate from the group and join another one with a better reputation. That group can either eat more abundantly (thanks to its opening of new territories for hunting and gathering), or be richer in decorations and tools thanks to trade exchanges with neighbors, or become more powerful as a result of a victorious military campaign ”[Levi-Strauss, 1984] ...

Leadership. One of the most important factors determining the fate of a group and, ultimately, its subsequent prosperity or complete disappearance, is the personal qualities of the leader of a particular group. Levi-Strauss calls such a leader a "leader", although he immediately stipulates that he does not, in fact, have any powers of authority. The word used by the Nambikvar for the leader of the group is literally translated as "the one who unites." In choosing a leader (whose office is not inherited from the Nambiquar - for example, from father to son), Indians pursue the goal of creating a viable collective, but by no means burdening themselves with centralized power. The degree of responsibility and range of responsibilities that fall on the shoulders of a leader many times exceed the privileges due to him, such as the right to have several "additional" ones in addition to one wife. By virtue of the above, it is not so rare that a man categorically refuses to take on the role of "leader".

“The main qualities of a leader in Nambiquara society,” writes Levi-Strauss, “are authority and the ability to inspire confidence. Those who lead a group during the dry, hungry season absolutely need these qualities. For seven or eight months, the leader is fully responsible for the group. He organizes the preparation for the trip, chooses the route, determines the place and duration of stops. He decides on the organization of hunting, fishing, collecting plants and small animals, he determines the behavior of his group in relation to neighboring groups. When the leader of the group is at the same time the leader of the village (that is, the place of temporary location for the rainy season), his duties are further expanded. In this case, he determines the beginning and place of sedentary life, directs garden work and chooses agricultural crops; in general, he guides the activities of the villagers depending on the seasonal needs and opportunities. "

However, in the event that the leader's miscalculations follow one after another, the discontent of his wards grows, and families, one after another, begin to leave the group. In such a situation, a moment may come when the few remaining men in the group are no longer able to protect its female half from the claims of strangers. And here the leader has only one way out - to join a larger and more successful group and thereby abandon his role as leader. Against the background of this constantly ongoing process of changing the composition of groups, the collapse of the former and the emergence of new ones, the only stable cell in the Nambiquara society is a married couple with their offspring.

Intergroup relationships. To complete the picture, it is necessary to say a few words about the relationship of nomadic groups with each other. It is essential that groups belonging to different communities can roam at the same territory at the same time. Such groups are not connected with each other by a network of kinship ties, and sometimes members of one and the other even speak significantly different dialects. In most cases, the relationship between such groups is based on latent antagonism, but if one of them or both are depressed due to their small size, the groups can unite and become related. However, as already mentioned, mutual distrust between groups roaming in the same territory (but belonging to different communities) is much more characteristic of the Nambikvar than good-neighborly or allied relations between groups.

Our brief excursion into the world of the Nambiquara Indians allows us to understand some general principles of the organization of a typical segmental society, devoid of any institutions of centralized power and management. A similar type of social organization has survived to this day among many ethnic groups with a variety of forms of primitive economics - hunting and gathering, slash-and-burn agriculture and pasture cattle breeding. At the same time, some ethnic groups completely rely on any one of these three life support strategies, while others practice different combinations of them - like, for example, the same nambikvara, which change from the dry season to the rainy one from hunting and gatherer to cultivation of agricultural crops. It is these differences between ethnic groups in the sphere of their economy that determine the characteristic features of the social organization of each of them, despite the fact that all the variations we observe one way or another fit into the framework of a single type of segmental anarchic society.

The role of kinship systems. Everything that has been discussed so far concerns mainly that side of the social organization of segmental societies, which can be called territorial, or spatial structure. In its architectonics, a hierarchy of structural units is clearly traced: segments of a lower level, together with similar ones, are added to segments of ever higher levels. For example, among the Nuers of East Africa, the social unit minimum level it turns out a woman with her children, as a rule, occupies a separate hut, in which her husband sometimes lives. In the latter case, we have before us the so-called small, or nuclear (from the word nucleus - nucleus) family. A group of close relatives (for example, several brothers with their monogamous or polygamous families) inhabit several huts, which together make up a manor or a farm. This grouping is usually referred to as the “big family”. The estates concentrated in one place form a village. The inhabitants of villages located in a particular sector of the Nuer country consider themselves members of a unity designated by ethnographers as a department of the tribe. The departments divide up the territory of the tribe as such. Nine large tribes and a number of smaller ones form the ethnos Nat (as the Nuers themselves call themselves), which numbered about 200 thousand people in the first third of our century [Evans-Pritchard, 1985].

Undoubtedly, without understanding the principles of the spatial organization of segmental societies, we will not be able to appreciate all of their originality. And yet the above descriptions outline only the outer side of the structures of interest to us, a kind of tip of the iceberg, relatively easily accessible to the eye of an outside observer. The very essence of the social processes taking place in all the societies we have mentioned and in others like them is based on a very complex set of rules of community, which are based on the so-called systems of kinship.

The fact is that in segmental societies, all life and activities of a person from birth to death takes place in a circle of persons, the overwhelming majority of whom are more or less close relatives. The reason for this, in particular, is that the largest territorial segment of society, such as a tribe, is an endogamous cell for most of the ethnic groups of interest to us. This means that tradition requires each member of the tribe to find a marriage partner (husband or wife) within their tribe. It is clear that with a tribe of only a few hundred people, whose ancestors occupied this territory for centuries, all people living here today, with the exception of a few newcomers, turn out to be in one way or another connected by blood ties.

Drawing a picture of social relationships in Nuer society, E. Evans-Pritchard writes: “Rights, privileges, obligations are determined by kinship. Either a person is your relative (real or fictitious), or it is a person to whom you have no obligations, and then you consider him as a potential enemy. Every person in the village and in the surrounding area is considered a relative in one way or another. Therefore, apart from the occasional homeless and despised vagrant, the Nuer communicates only with people who behave towards him like relatives. "

Legal regulations. The study of ethnic groups that have retained the features of the primitive communal system in their lives is always an excursion into the world of amazing beliefs, customs and rituals that are often poorly understood by an outside observer. But what is most surprising is the ability of such societies to maintain a stable internal order in the absence of any explicit instruments of legislative, executive and judicial power. In an egalitarian society with primitive forms of economy, a person considers himself equal to everyone else and is not inclined to obey any dictates from his neighbors. When Miklukho-M-aklay asked the inhabitants of a Papuan village who their leader was, every adult man invariably pointed to himself.

In such a situation, the main sources of maintaining public order are, firstly, the habit, absorbed with mother's milk, to adhere strictly to the time-honored rules of dormitory, and, secondly, the shared understanding that, in resolving conflicts, a compromise between community members is obviously preferable. violence. For in a small, close team, the cohesion of which is opposed to the aggressiveness of the outside world and forms the very basis of survival, any discord is like a cancerous tumor. More and more new participants will gradually be drawn into the conflict, which leads to the escalation of tension in relations between everyone and everyone and threatens, ultimately, with the collapse of the community.

Therefore, in many archaic societies, there is a belief that discord and quarrels between group members invariably damage all its well-being. “Anger,” writes L. Levy-Bruhl, in particular, “perhaps most of all confuses and worries primitive people. This is not due to the violence that he can entail, as we might think, but because of the fear of the bad influence that he brings down on the whole society, or, more precisely, before that harmful beginning, the presence of which finds himself in a rage of a person who is in anger. " For this reason, it is rarely seen that in the societies in question, a person openly contradicts the interlocutor.

It must be said, however, that the categorical condemnation of violence in relationships between community members is not a common feature of all those ethnic groups whose social structure and basic moral principles have been sufficiently well studied and understood. Indicative, in particular, is the opposition carried out by the famous ethnographer, American M. Mead between the two ethnic groups of New Guinea: the Mundugumors and the Arapesh. “I was disgusted with the culture of the Mundugumors, with its endless struggles, violence and exploitation, dislike of children,” Mead writes. "The dominant type among the Mundugumors was ferocious money-grubbing men and women ... Both men and women were expected to be openly sexual and aggressive." In contrast, the Arapesh have raised everyone from childhood in a spirit of complete responsiveness to the needs of others, so that the mildest condemnation from the community is enough to force the egoist to cooperate. In the culture of the arapesh, the type of selfish screamers, "whose ears are closed, and their throats are open," is unconditionally condemned, while the most useful members of society are considered modest, balanced and taciturn people, "whose ears are open and their throats are closed."

Of course, the possibility of an absolutely conflict-free society is just an illusion, albeit a fairly widespread one. Always and everywhere, the interests of the individual in one way or another come into conflict with the interests of other people, and this causes not only banal quarrels and squabbles, but sometimes can lead to the most serious consequences - for example, to murder. The question arises whether there are any public sanctions against the killer in a community devoid of central authority and judicial authorities. And in general, how in such conditions can control over antisocial behavior that violate the normal course of life of the entire team be exercised? We find an exhaustive answer to these questions in the works of E. Evans-Pritchard, already known to us, who paid special attention to all possible forms of conflict in the society of African pastoralists - Nuer.

As I already said, this ethnos is split into several tribes, and one of the important features of a tribe as a real segment of society is the existence in it of the right to compensation for murder - the so-called "vira for blood". The murder of a member of another tribe by a Nuer is not in any way condemned in the circle of the murderer. How to avenge the murdered is a problem of outsiders, who are usually viewed in the community as potential military adversaries. If a person kills a resident of his own or a neighboring village, the danger of a blood feud becomes real. The relatives of the slain will be covered with shame if they do not devote all their energy to his revenge. In this case, any male relative of the killer can become a victim. And as soon as all the inhabitants of a village or district are, to one degree or another, related to each other, a multitude of people are automatically drawn into the confrontation between the two lineages. This situation is completely intolerable for the community. According to Evans-Pritchard, the fear of causing blood feud is the most important mechanism for maintaining law and order within the community and the main guarantee of the safety of an individual's life and property. It is the task of the so-called "leader in the leopard's skin" to prevent the deepening and spreading of the conflict caused by the murder.

The role of this character is nothing more than the role of an intermediary in negotiations between the killer and the relatives of his victim. The Nuers themselves, apparently, do not experience the slightest admiration for this figure performing purely ritual functions. "We chose them, gave them leopard skins and made them our leaders," the Nuer say, "so that they can participate in the sacrifices on the occasion of the murder." The leader is not able to force the parties to go to the world force of his authority, because no one can force the Nuer to take any step against his will. Nevertheless, the positive outcome of the negotiations was actually a foregone conclusion. As long as there is nothing worse for the members of the community than a sustained blood feud, the consent of both sides will almost certainly be obtained. However, the leader usually has to spend a lot of time and energy in order to persuade the relatives of the murdered to the world, because in order not to lose dignity in such a delicate matter of honor, they should show a certain stubbornness. “Nuer is proud,” they say, “and does not want cattle (as compensation - EP), but a human body in revenge for the murdered one. Having killed a person, he pays his debt, and his heart rejoices. "

Emergency resolution of conflicts that can generate blood feud among the Nuer is relatively easy to implement within the village or when friction arises between the inhabitants of neighboring villages. However, if enmity arises between larger territorial segments of society, such as tribal departments, several people can die immediately in a clash between them. At the same time, there are often no directly interested persons who would be ready to immediately enter into an intermediary for the payment of compensation. The relatives of the killed are simply waiting for a new clash in order to avenge all their losses in full. In such a situation, the crack between the segments widens until the positive contacts between them cease completely. As a result, the initially single tribe splits into two, which do not have any obligations in relation to each other.

Splitting the community. For the Nuer, a village is not just a place to live. Each homestead includes livestock pens, pastures and plots used for planting crops. Therefore, a family in a state of growing conflict with other residents cannot afford to simply leave its place and settle down somewhere else. The situation is different with forest farmers, such as, for example, the South American Yanomama Indians, whose plantations are often located at a considerable distance from the Shapuno village. Among these Indians, who have earned the reputation of "fierce people" for their belligerence and imbalance, a one-time splitting of the community is quite common. Men are extremely quarrelsome and vindictive, and even a minor disagreement between them can easily develop into mutual intolerance. Relatives from one side and the other are inevitably drawn into the latent enmity. The denouement often comes after the warriors, during their evening leisure hours, smoke epen, a special powder made by yanomama from poisonous plants and causing hallucinations. In a state of intoxication, enemies invite each other to a competition in strength. A tragic denouement occurs only if one of the participants grabs the bow. The Indians, as a rule, use arrows with jagged points, poisoned with curare poison. So a well-aimed shot almost inevitably entails the death of an enemy, and a miss can easily turn into the death of one of the involuntary witnesses of what is happening.

Such excesses inevitably entail the departure from the community of a whole group of people linked by kinship, common interests and the strength of the authority of the warrior taking on the role of leader in the separating group. It was shown that the splitting of the community is most realistic to expect after the number of its members reaches about a hundred people. With a population of 40-60 people, the village can put about 10 waiteri men (as the Yanomama warriors are called) as a combat detachment to protect themselves from the raids of neighbors. This is obviously not enough, given the climate of mutual mistrust, deceit and unpredictability prevailing in relations between communities. Two such units make the community less vulnerable and allow more successful raids on neighbors to kidnap the women there. Two dozen fighters correspond to the total community size of about 100 people. However, with its further growth, the likelihood of internal strife increases sharply, and it is at this stage that the community usually splits - like those processes of sociotomy, or desmosis, which are described in the populations of social insects and some species of monkeys.

Xenophobia and War. If the usual state of a community in a segmental society is peace, only sporadically darkened by short-term outbursts of anger and violence, then the relationship between communities looks quite different. This is what N.N. Miklouho-Maclay on the general social climate on the northeastern coast of New Guinea: “The wars here, although they do not differ in bloodshed (there are few killed), are very long, often turning into the form of private vendettas that maintain a constant wandering between communities and greatly delay the conclusion of a peace or truce. During the war, all communications between many villages stop, the prevailing thought of everyone: the desire to kill or the fear of being killed ... Security for the natives of different villages is still a cherished dream on my Shore. Not to mention the mountain dwellers (who are considered especially warlike), but between the coastal states of affairs is such that not a single native living at Cape Dupere dares to walk along the coast to Cape Rigny, which is 2 or 2, 5 days of walking. "

This is how the situation looked in the 70s of the last century, but it did not undergo significant changes, at least until the 30s of this century, when American ethnographers began to work in New Guinea. So, M. Mead in the following words describes the attitude to the Chu-Zhaks among the mountain arapes living a little west of the Maclay Coast: “The children of arapesh grow up, dividing people in the world into two large categories. The first category is relatives - three or four hundred people, residents of their own area and residents of villages in other areas, associated with marriage and long genealogical lines ... The second - aliens and enemies, usually called varibim, people from the plains, literally - "people from the riverside land". These people from the plains play a double role in the lives of children - a scarecrow, who must be feared, and an enemy who must be hated, ridiculed, outwitted - creatures to whom all the hostility that is forbidden in relations between members of their group is transferred ”(detente and italics M. Meade).

Xenophobia soaked in mother's milk is extremely characteristic of the primitive consciousness of members of segmental societies around the world. It is rooted, firstly, in the militant ethnocentrism of economically backward peoples, in their ideas about their superiority and exclusivity, and, secondly, in the unshakable conviction that all the misfortunes that threaten a community stem from the witchcraft of alien neighbors. The feeling of invisible danger constantly emanating from there, threatening you and your loved ones, colors with an unaccountable feeling of fear a person's entire life from birth to the grave. The cause of illness or death is seen here in the fact that the victim, through negligence, left somewhere a particle of his "dirt", which was found and bewitched by enemies from the neighboring community.

It may seem surprising that only in a few segmental societies (such as, for example, the mountainous micro-ethnos Aipo in western New Guinea), wars between communities are directly engendered by their competition over space - in particular, by protecting their territory from outsiders. The reason may be that the structure of family relations (clan and lineage) in these societies carries a much more important psychological load than the spatial, territorial structure. Among the Australian aborigines, the territory of the so-called local hereditary group is determined not so much by its borders as by those specific areas that the group has owned from time immemorial. Other groups are not forbidden to hunt within this territory, but they are strictly forbidden to approach those places that are related to the cult totemism of the group (these can be caves, the walls of which are painted with ocher or blood, as well as specific rocks, trees, water sources, etc.). For the Bushmen of the Kala Hari Desert, the boundaries of territories belonging to large segments of society (the so-called nexus) are inviolable, while on the territory of a local group it is allowed, albeit with reservations, to hunt other groups that are part of the same nexus. According to some observers, among the Bushmen and pygmies of the Ityri Forest in Zaire, who also lead a life of hunter-gatherers, neighboring groups plan their movement in such a way as to avoid contact with each other as much as possible.

In the attitude of a hunter and gatherer or a forest farmer to his land, according to M. Mead, "there is nothing from the proud possessiveness of the landlord, vigorously defending his rights to it from all newcomers." The New Guinean arapesh, like the aborigines of Australia, the land belongs to the spirits of their ancestors, and the people themselves belong to this land. Papuans from the Alitoa community discussed the situation in the neighboring village, the population of which has clearly declined in recent years: “Oh, poor Alipingale, when its inhabitants die, who will take care of the land, who will live there under the trees? We must give them children so that they can adopt them, so that this land and trees have people when we die. "

If in segmental societies they usually do not fight over land, what are the material reasons for the constant wars between communities against the background of that xenophobia that determines the entire psychological mood of individuals? Obviously, these reasons are different in different cultures. For example, among the Yanomama, according to these Indians themselves, the main, if not the only purpose of military raids on neighbors is the kidnapping of local women. Monogamous marriage is not honored in the Yanomama, and most men have several wives, acquired mainly by force [Ettore Biokka, 1972].

The Nuers of East Africa are no less aggressive and militant than the South American Yanomama, but the main goal of their inter-tribal wars and predatory raids on communities of other ethnic groups is the capture of livestock, although girls and women of marriageable age are also among the spoils of war. War, according to E. Evans-Pritchard, is the second most important activity of the Nuer after cattle breeding. A routine way of spending time and even a kind of entertainment for the Chin Nuer men is the periodic robbery raids on the communities of the neighboring Dinka people, associated with the Nuers by common ethnic roots. The Dinka, like the Nuers, live by cattle breeding, but they obtain livestock mainly by theft and deception, and not by force of arms, as the Nuers do. Therefore, the latter are not afraid of the Dinka, despise them, and do not even take their shields from them, going on a campaign against the numerically predominant enemy. Boys, who are taught from early childhood in Nuer society to resolve all disputes by fighting, dream of the time when, immediately after initiation, they can take part in a campaign against the Dinka and thereby quickly enrich themselves and acquire a reputation as a warrior.

The motives underlying intercommunal and intertribal enmity among some ethnic groups of New Guinea do not look as frankly mercantile to us as those that give rise to wars among the Yanomama and Nuer. Here, legalized by the age-old tradition, the hunt for people from among the "outsiders" does not require any justification of the economic order. It is closely intertwined with the daily life of the community and harmoniously fits into the whole system of archaic beliefs and bizarre rituals that determine the identity of the individual and the entire ideology of the local primitive culture. I mean the so-called "headhunting", which is practiced to this day by the Asmat Papuans living in the southwestern part of New Guinea. Asmat literally means “true people”. Such self-esteem, however, does not prevent these Papuans from regarding the head of their fellow tribesman from another community as a full-fledged hunting trophy, and not just the head of a white-skinned alien (for example, a missionary), who is not considered to be true people here.

These Papuans live in comfortable villages, each of which must have a so-called men's house, which is a kind of club for all kinds of ceremonies and rituals. The number of inhabitants in these villages ranges from several hundred to one and a half thousand people. There is usually no good-neighborly relations between the villages, and the communities that make up them are in a state of constant enmity with each other. This is understandable, since, according to local custom, the initiation (initiation into a man) of each boy in the village requires as a necessary condition for the acquisition of the next trophy - the head of one of the men of another community. It is important that the name of this person must be known in advance by his killer, since this name will be assigned to the young man at the time of initiation. Together with the name, the strength, energy and sexual potency of the killed must also go to him. Of course, each episode of the death of a member of one community sooner or later entails a retaliatory act of revenge, so that the losses of both sides are steadily increasing. Periodic commemoration of the victims of this kind of partisan war is poured out in each community into a complex, multi-stage ritual.

More recently, headhunting was also practiced by other ethnic groups of New Guinea (such as, for example, the Chambuli and Abelams in the north of the central part of the island), as well as by the inhabitants of the islands of Mikronesia and Melanesia in the southwestern sector of the Pacific Ocean. For example, on the Palau archipelago (Caroline Islands), which lies about 1,000 km northwest of New Guinea, the political situation in the last third of the last century looked, according to N.N. Miklouho-Maclay, as follows. “Wars,” the scientist wrote, “are very frequent in the archipelago, and the most insignificant reasons are considered sufficient for waging them. They significantly affect the decrease in population, since there are many areas independent from each other, and all of them are constantly at war. These wars are more like head-hunting expeditions and, it seems, are even predominantly waged for this purpose. "

Miklouho-Maclay especially emphasized the "vile", in his words, way of waging wars among the natives. He writes that in their ideas “... any cunning, deception, ambush are considered permissible; it is not even in the least considered humiliating if one person is killed with the help of a large number of people, even a woman and a child. The main thing is to get the enemy's head ”(Miklouho-Maclay's italics). The absence of any moral and ethical obligations to "outsiders", even if they belong to the same ethnic group and the same culture, and the resulting naively cruel, infantile disregard for the value of human life - these are the features that are common to all those anarchic societies of Africa, South America and Oceania, which passed before our eyes. Alas, the echoes of these barbaric customs still exist in our "developed" industrial society, but here the individual's safety is guarded by law and law and order, which, unfortunately, are often violated.

Observing the customs of the Nambikwara, Yanomama or Asmat, how not to recall the following significant remark of M. Mead: is present in the inhabitants of one country and absent in the inhabitants of another, although the latter may belong to the same race. "

Towards the formation of the state

Most of those social organisms that have passed before our eyes are among the so-called self-sustaining societies. This means that people here in each given period of time consume everything that they extract or produce to maintain their existence. In this respect, especially indicative are the societies of hunters and gatherers, as well as forest farmers, whose technical equipment is at the stage of the Late Stone Age. Agricultural crops grown on forest clearing by the Papuans and New Guineas or by the Yanomama Indians, for the most part, are fruit or tuberous plants, the harvest of which, unlike grain crops, does not lend itself to long-term storage. Therefore, the accumulation of any surplus is, in principle, impossible or very limited, so that the community is always in danger of hunger.

Societies that practice primitive forms of pasture cattle breeding are in a somewhat better position. Livestock is a kind of capital that can be accumulated and used for exchange. However, even having a large herd does not solve the problem of daily good nutrition. The Nuers, for example, only in the most exceptional cases decide to slaughter a cow, and they, according to Evans-Pritchard, have only one step from complete satisfaction of needs to need and malnutrition.

It is difficult to remain indifferent at the sight of an unusually variegated and multicolored picture of the diversity of archaic societies, only a small fraction of which I have been able to touch on on the previous pages. However, no matter how unique the way of life, manners and customs of each of them are, in this infinite diversity we still managed to distinguish, perhaps roughly and conditionally, three main types of socio-cultural formations. I mean, firstly, hunter-gatherer societies, secondly, rainforest farmers and, finally, societies that practice the simplest methods of pasture cattle breeding. In other words, the most important features of each of these three types of societies are determined, first of all, by the methods of their life support and production. The entire sum of production skills, mutually related to the material culture dominating in a particular society (which includes tools of labor, dwellings, household items, etc.), can be called civilization. It is in this sense that the French ethnographer J. Macke speaks, in relation to the three named types of societies, about the "civilization of the bow", "the civilization of the forest" and the "civilization of the spear."

Speaking about the fourth type of society, namely about the "civilization of granaries", J. Mac has in mind a completely definite circle of African ethnic cultures. These are Bantu-speaking Negroid ethnic groups living in the area of the African savannah south of the equator (lunda, luba, bemba, lozi and a number of others, which make up a significant part of the population of southern Zaire, Angola and Zambia). The most important difference between the peculiarities of agriculture in the civilization of the forest, on the one hand, and in the civilization of grain storage, on the other, is determined by the composition of agricultural crops. Forest farmers specialize mainly in the cultivation of tuberous crops (sweet potatoes, yams, cassava), the harvest of which is difficult to store. As for the inhabitants of the savannah, they, not completely abandoning the cultivation of tuberous, focused mainly on crops of cereals - such, in particular, as sorghum and millet. And since long-term storage is guaranteed to the grain harvest by nature itself, people have the opportunity to store it for future use. According to J. Macke, during the transition from forest farming to agriculture in the savannah, a line was taken that ensured the accumulation of surpluses. It was also important that portions of grain, due to their flowability and homogeneity, are convenient to measure, transfer from hand to hand in strictly comparable quantities and transport over long distances. It is clear that this circumstance increases the opportunities for exchange and establishment of connections between communities distant from each other - in contrast to what we have seen, say, among the farmers of the rainforest.

The possibility of accumulation of surpluses with fatal inevitability gives rise to material inequality of people, on the nutritious soil of which the real fall in society grows together with the bureaucracy serving it. The egalitarian society of primitive communism, step by step, grows first into a kind of pre-state formation, and then, under a certain set of circumstances, into a centralized state with a more or less developed administrative system of management of all its subdivisions. A segmental society, consisting of communities of equal value to each other, turns into a hierarchically organized pyramid, where the privileged elite dominates the vast periphery. Ethnographers could observe all the stages of this process of the birth of the state with their own eyes on the example of agricultural societies in the southern half of Africa, to which we will turn after J. Mac.

In the villages of the inhabitants of the African savannah, the traveler is immediately struck by the large, clay-coated baskets standing on the wood scraps next to the huts. By the number and size of these baskets-granaries, at first glance, one can determine the degree of well-being of the inhabitants of a particular dwelling. It is also clear that the richest granaries belong to the head of the community. However, one should not think that all their contents are certainly the personal property of the latter. The stocks stored here, made up of the peasants' surplus crops, are intended for public use during village festivals or in case of crop failure. It is also important that the possession of such a reserve frees up the leader's time to engage in a wide variety of affairs of community management and the improvement of the village. As if in return, he demands from residents further replenishment of supplies, which, ultimately, provides the leader with more and more effective means of pressure and coercion. So, step by step, the leader acquires real political power and becomes a leader in the full sense of the word.

With the growth of the well-being and power of this or that leader, his appetites grow, and he, with the help of his associates, or even military force, seeks to spread his influence over neighboring communities, one way or another suppressing the leaders there. This process of centralizing political power goes through several successive stages, so that hierarchically organized political structures are formed over time. For example, in Zambia today, several dozen villages with a total population of about 5-10 thousand inhabitants make up the so-called chiefdom, under the rule of a leader of a relatively low rank. He, along with other leaders of equal status, is subordinate to a higher-ranking leader, who already controls several chiefs. Among the people of Cuba, until recently, the political organization was a union of leaders who dominated their own territories and at the same time recognized the power of the so-called Nyimi, the leader of the Mbala tribe. A political organization of this type can be called a federal proto-state, rallied under the auspices of one of the leaders. Societies of this type, with all sorts of particular variations, have arisen and disintegrated many times throughout the history of tropical Africa.

Under such a system, the power of the leader is based on four foundations. This is, firstly, wealth, which is determined by the number of villages belonging to the leader and, accordingly, by the contingent of workers to cultivate the fields and combat-ready young men. Further, the strength of the leader's influence depends on the size of his entourage, which constitutes the layer of nobility and bureaucracy. In addition, he has the right to administer the court and seek the execution of the sentence by means of coercion. Finally, the leader is surrounded by the halo of the omnipotent magician. According to the American ethnographer V. Turner, among the Ndembu people in Zambia, the supreme leader “... is at the same time the top of the political and legal hierarchy, and the entire community ... Symbolically, he is also the most tribal territory and all its riches ... The fertility of the land, as well as the protection of the country from drought, hunger, disease and insect raids are linked to the position of the leader and to his physical and moral condition. "

It is important to emphasize, however, that for all this omnipotence of the leader, his position in society largely retains the echoes of earlier systems of universal equality. This becomes especially obvious when one gets acquainted with the ritual of initiation into the leader, the first stage of which, according to Turner's descriptions, is a procedure that, from our point of view, is extremely humiliating for the future ruler. Here are just some excerpts from the high priest's monologue addressed to the newly-minted leader. “Shut up! You are a pitiful selfish fool with a bad temper! You don't love your friends, you just get angry with them! Meanness and stealing are all that you own! And yet we have called you and we say that you must inherit the leader. Having renounced meanness, give up anger, give up adultery, immediately give up all this! .. If earlier you were mean and used to eating your porridge and meat alone, today you are a leader. You must give up self-love, you must greet everyone, you are the leader ... You must not judge with partial judgment in the affairs in which your loved ones are involved, especially your children. "

At the end of this speech, each of those present has the right to shower the chosen one with abuse and, in the most harsh expressions, recall to him all the insults he has inflicted. At the same time, it is assumed that the leader will not be able to recall any of these insults to his subjects in the future. Not limited to verbal attacks on the initiate in power, the high priest also resorts to physical influence on him, from time to time slapping the leader on his bare buttocks. It is impossible not to admit the truth of the statements of eyewitnesses of this whole scene, who say that on the night before entering the dignity, the position of a leader is equated with the lack of rights of a slave. The described ritual has a double meaning. First, it symbolizes the “death” of the future leader as an ordinary member of society. Secondly, from now on, the leader should consider all his privileges as a gift of the community, which should be used for the collective good, and not for the satisfaction of his own interests. Even when a person becomes a leader, he must remain a member of the community of people that chose him, “laughing with them,” welcoming everyone and sharing food with them.